Grappling with the death of her father and feeling cut off from her Māori roots, Dr Karyn Paringatai decided to find her wider whānau. It proved to be a life-changing and life-saving choice, which led to her being diagnosed as a rare CDH1 gene carrier and having her stomach removed.

“There are a whole lot of valid reasons why Māori are disconnected,” says Karyn, 43, who lost contact with her extended whānau as a child when her dad, like so many Māori of that generation, distanced himself and his daughter from their culture and language.

“I totally get why, but if I didn’t decide to reconnect, I was sitting on a ticking time bomb playing genetic jeopardy with my life.”

It was on a rare visit back to her marae Mātahi o te tau in the East Cape to commemorate her dad’s life after he died of a heart attack in 2007 that the Dunedin mother learnt about her whānau’s health history with gastric diffuse cancer and was told to get tested for the CDH1 gene mutation.

Carriers have a startling 70 to 80 percent chance of developing stomach cancer and Māori are three times more likely than those of European descent to be affected.

“At first, it didn’t really hit home for me because I hadn’t yet seen anyone die of this cancer. It hadn’t affected me – until I tested positive,” recalls Karyn, who was shocked with the results and the recommendation she have her stomach removed.

“When I met with the surgeon, I was in the middle of my PhD, Dad had just died, I had two stepkids and was just trying to survive grief when this bombshell dropped on me,” shares Karyn.

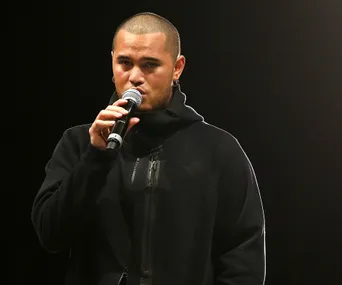

With partner Neihana Matiu.

In June 2010, she had her stomach removed in a roux-en-y procedure, which connected her oesophagus directly to her small intestine. She describes the stomach as a storage pit and explains instead food is now digested directly in her intestines. Musician Stan Walker had the same procedure and publicly shared his journey in a documentary after being diagnosed with early-stage stomach cancer in 2019.

Post-surgery, there were plenty of challenges for Karyn – dizziness and severe discomfort as her body processed food without a stomach, rapid weight loss, and initially things like bread and even water were really hard to swallow.

“There’s a lack of understanding when a few months down the track you look gaunt and people ask if you’re on drugs or sick,” tells Karyn.

Now, the University of Otago lecturer can eat most foods, and lives a full life dedicated to helping other gene carriers and their whānau.

Her research focuses on the impact of whakapapa (Māori ancestral knowledge) on early detection of the gene and the deadly disease.

Karyn’s research will benefit her kids and other families.

Karyn believes if not for her decision to connect with her whakapapa, she may not be alive today.

“It happens underneath the stomach lining, so often you don’t know anything is wrong until stage four or five and by that time, there’s little hope for survival if it has jumped to other organs. It’s a really silent killer,” says Karyn, whose tamariki Manuhou, three, and Mātahi, one have a 50 percent chance of also having the gene.

“If I died tomorrow, I need to make sure I’ve done everything possible to set up support structures for my children when they get tested so if they’re positive, they have whānau who can rush to their sides and help them with the surgery.”

Testing is available for Māori from age 14 if at least one person in the family has been diagnosed with stomach cancer, but Karyn believes earlier screening could save more lives.

“One of my cousins, Evelyn, died from it when she was 33,” she says. “She had two young kids and one was only six months old. Think of her husband with two babies. He saw his wife die and then had to wait for 14 years before he could get his kids tested, every day living in fear.”

The loving mum will have Mātahi (left) and Manahou tested for the gene mutation.

In this case, the whānau’s worst fears were realised. At just 14, one of the sons was diagnosed with the cancer and had his stomach removed immediately.

Since her own surgery, at least 20 other relatives have gone on to take the test – and it’s personal experiences like this that fuel Karyn’s drive to continue researching in the hopes her work will help save others’ lives.

“I wasn’t brought up with whānau, te reo or tikanga [customary practices] in our home and I didn’t ever think this little girl from Invercargill would be able to make real change,” says Karyn.

“I’m doing this for the kids, making sure I put in place support structures and systems not just for my children, but for all our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren to come. This cancer is not going away, the gene can’t be fixed, so we have to manage it as best we can.”

To find out more or access support, visit the Gut Cancer Foundation website.