On New Year’s Day 1998, young Marlborough friends Ben Smart and Olivia Hope disappeared after boarding a mystery yacht with a stranger. Scott Watson was convicted of their murders, but the case remains one of the most controversial in New Zealand’s history. For 18 years, Watson has maintained his innocence and kept his silence. But in 2014, he invited North & South writer Mike White, who was a reporter on the Marlborough Express when Ben and Olivia went missing and has covered the case from the very beginning, to interview him in prison. The authorities sought to prevent the meeting, and it took more than a year and a hearing in the High Court to get that decision overturned. Now, for the first time, Scott Watson tells his side of the story and what happened that night in the Marlborough Sounds.

This is what 18 years looks like. In those early photos of Scott Watson as he walked to court, he looked just like a million other young guys, flashed up and slightly self-conscious. His hair is dark and combed to the left. He’s wearing a dark suit with scarlet tie. He could be anyone’s son, brother or uncle, with things to do later that day, and plans for getting ahead.

Now he looks like a guy who sells fridges at Noel Leeming. Like someone in charge of the produce department at Pak’nSave. Still your average guy, but someone whose prime is past. The hair is greying and there’s not really enough to comb any more. The dark eyes now look through wire-framed glasses. He looks more solid, more stocky. He looks dispiritingly middle-aged.

Scott Watson is 44 now. When he appeared in the High Court at Christ-church in May this year to challenge the Corrections Department’s attempt to stop this story being written, it was the first time he’d been seen in public since he was sentenced to life imprisonment for murdering Ben Smart and Olivia Hope. Other than his family, nobody recognised Watson as he took a seat beside his lawyer, Kerry Cook. That’s what 18 years does – you change far more than you realise, and people forget how you once were.

But people haven’t forgotten Watson’s case, and in those 18 years, doubts about whether he is guilty have continued to grow. Until now, though, he’s never spoken about what happened, trusting the justice system would finally exonerate him, trusting his lawyers’ advice to remain silent. Until now. Until now, sitting in a room in Rolleston Prison, wearing a grey T-shirt, green fleece top, grey sweat pants, and gym shoes with holes in them. A middle-aged guy with 18 years of memories and resentment bottled up inside.

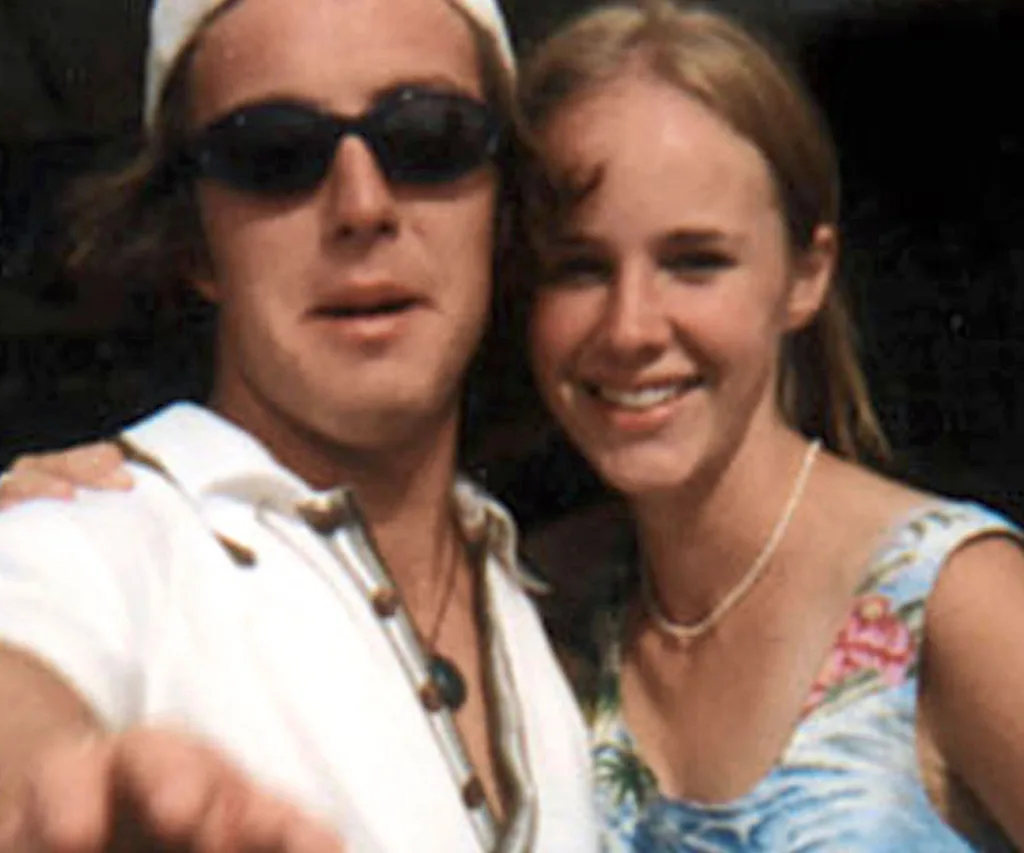

Ben Smart and Olivia Hope saw in the New Year at Furneaux Lodge in the Marlborough Sounds, but disappeared hours later. Their bodies have never been found.

Olivia Hope arrived at Furneaux Lodge in the Marlborough Sounds on the afternoon of December 31, 1997. The 17-year-old Blenheim student had just finished college, and was working at a winery over the holidays before heading to university in Dunedin. Along with her older sister, Amelia, and a group of friends, she’d chartered a yacht, Tamarack, for a few days, with the New Year’s party at Furneaux being the highlight.

Ben Smart was staying across Endeavour Inlet at a bach in Punga Cove. He was 21 and had been living in Christ-church, but knew Olivia socially. He’d driven to Punga Cove in his Mini and had been partying with mates before catching a boat across to Furneaux Lodge for the renowned celebrations.

Scott Watson had set out from Picton that morning on his yacht Blade, and arrived at Furneaux mid-afternoon. Watson, 26, had grown up living on board his family’s yacht, had owned boats himself and had built Blade in the backyard of his parents’ Picton home. It took him only a year, working in his spare time, to construct the 26ft sloop, which had become his home.

“I wanted to go sailing. People spend 20 years, 30 years building a boat – their entire lives. There’s no point in doing that, is there? If you want to go sailing, you get stuck in and finish it.”

He chose steel for the hull for strength, so he didn’t have to pay insurance. “Wooden boats, if they sit on the rocks, one day they’ve got a hole in them, the next day they’re in pieces this big, the next day they’re in pieces this big,” he says, bringing his palms towards each other. As he does so, you notice his right hand where he’s lost parts of two fingers – one in a hatch on his parents’ yacht, one in a water pump.

In early 1997, he trucked Blade to a boatyard near the Picton ferry terminal, sandblasted and painted the hull, and launched it. He rigged it, added ballast and, on the shortest day of the year, headed north, with few plans other than to “just go for a sail”.

“And there was an outrageous storm, 50 knots or something. So we pulled into Wellington and all the rain was horizontal – so it was a good move.”

June 1998: Scott Watson is taken to the Christchurch District Court in a police car before being charged with the murder of Ben Smart and Olivia Hope.

For the next few months, he poked around up north, living on board and picking up jobs wherever he went. By December, Watson had sailed back to Picton, planning on spending time around the Sounds, doing a bit of work, and tidying up Blade. He’d taken a long time deciding on a name for his yacht but had never written it on the hull.

“Names are a pain in the arse because you’ve got to paint around them to do things. The only real time you needed a name was when you went to a harbour and tied up at a marina and they’d say, ‘What’s the name of the boat?’ And I think I’ve called it this, that and everything. But I liked Blade.”

He thought about sailing to Ship Cove for New Year’s but friends mentioned they were going to Furneaux, so Watson figured he’d head there, aware it was a decent place for a party.

He bought supplies from the Picton supermarket and motored down Queen Charlotte Sound, stopping to cook lunch, and hooking a barracuda along the way.

When he arrived at Furneaux, Watson tossed his anchor overboard with all 30 feet of chain, only to have another bloke on a nearby yacht motion him to come over and raft up with them. Dave Mahony had known Watson since he was a kid and was skippering the charter boat Mina Cornelia, which had eight passengers aboard. They had a few drinks together, then Watson rowed over to another yacht, Unicorn, where his friends were, and continued drinking with them. At some stage, one of the passengers on Unicorn was searching for her handbag and Watson remembers dubbing her “the bag lady”, which didn’t go down well.

“It was a joke – but she didn’t get it.”

After that, he went back to the Mina Cornelia for more drinks. There was a joint being passed around, and about 10pm everyone headed to shore and the bar. Watson sort of remembers security staff stopping him from bringing his bottle of rum to the lodge, and drinking it on the wharf, but not a lot else.

“Nah, not really. Just got pissed. I was pissed, so was everyone else. It was a New Year’s Eve party, in the middle of nowhere. But I definitely wasn’t the only drunk person there. I definitely wasn’t the only drunk person there saying ham-fisted comments to women about their tits and their arses. But at no stage was I running round like Zac Guildford with my clothes off.” Pissed, a bit belligerent, and trying to chat up women, Watson inevitably offended some people. In one incident, he bailed up a young guy wearing a pearl necklace.

“What’s that Johnny Cash song? ‘A Boy Named Sue’? You heard that? Okay, so here was a little rugby-playing 18-year-old wearing a pearl necklace. And he goes to a pub with a whole lot of drunk people? He’s going to get some shit. He said afterwards that it belonged to his poor sister that died. I feel sorry for the guy about that. I feel for his family.”

According to the police case, Watson went back to Blade around 2am, somehow came back to shore unseen, then returned again to his boat around 4am in a Naiad water-taxi driven by Furneaux Lodge barman Guy Wallace.

Meanwhile, Ben and Olivia had gone to Tamarack but found nowhere to sleep. When Wallace dropped off other passengers at Tamarack, Ben and Olivia boarded the Naiad, intending to head ashore again. But police say it was Watson who offered them a place to sleep on his yacht, and the last they were seen was climbing aboard Blade with him. Watson, however, has always been adamant he returned to his yacht only once that night, on a water-taxi driven by an older guy. “I vaguely remember a guy with a sort of cowboy hat on and, like, a Swanndri.”

This description fits another of the water-taxi drivers, John Mullen, but Watson can’t say if it was him or not. That night’s booze and 18 years have dulled many memories.

“But it definitely wasn’t Guy Wallace. And it wasn’t a boat full of people – I’m definite about that.”

Watson says he clambered back on board Blade, which was alongside Mina Cornelia, with another yacht, Bianco, on the other side. “I remember jumping on their boat, next door, saying ‘Hey, what’s going on?’, because I thought they might still be up, being boaties. But they weren’t really boaties, they were charter-boat people. Then I jumped on the next boat over, and they were Auckland boaties.” They told him to piss off.

“But I never sat there for 30 seconds in their hatchway – coz that’s what they said. I remember I was lost for words – I thought, ‘Oh, that’s a bit rude.’ And I’d just been kidding them. So I just left.”

Watson says he went back to his boat, had a feed and crashed out. No going back to shore a second time, no Ben and Olivia, no rape, no murder.

Part of the problem with pinpointing exactly when Watson returned to Blade is that he didn’t have a watch – he hadn’t really worn one since he was a kid. “I was never in a hurry to go anywhere. It’s not a crime not to wear a watch. Bugger watches. They compartmentalise you into little segments.”

So he guessed it was around 2am when he got back to Blade. But others estimated the incident over the pearl necklace took place around 2.45am – allowing the police and Crown to claim Watson must have returned to shore after failing to rouse his neighbouring yachties for more drinks. However, there has never been any proof of how he got to shore.

Watson accepts it may have been 3am or even a bit later when he returned to Blade – he was drunk, he didn’t have a watch, a New Year’s party was hardly a place for clockwatching. And not having a watch or appointments to keep meant he was never certain about what time he woke up and motored away from Furneaux Lodge. “It was just crystal clear and calm,” so he figured he’d make the most of the day and head to his mate’s place in Tory Channel, where he’d arranged to pick up some paint for Blade.

A family later claimed they saw Blade near Marine Head at the entrance to Endeavour Inlet, with Watson acting strangely on board. “They were adamant it was me. But it wasn’t me. Didn’t happen. That was one of the wake-up calls of the whole trial – to have someone saying, without a doubt, I was in this place. I was thinking, what the hell? Absolute garbage.” One of the witnesses was a religious minister, and Watson said it was virtually impossible to challenge him. “That’d be like insulting God, wouldn’t it?” He insists he wouldn’t have anchored anywhere en route because it was such a hassle to pull up the anchor and chain, not having a winch on his yacht, but says he may have stopped for a short time, to go to the toilet or have breakfast.

“Just turn everything off and just sit there. Put on some music, put your head out every now and again and make sure you’re not getting run over by one of the crazies, coz the place goes crazy for two weeks over Christmas – there’s just this mist of two-stroke oil; you could smell it.” Watson guessed he left Furneaux about 6.30am and would have arrived at his mate’s place in Erie Bay, halfway down Tory Channel, between 9.30am and 10am. His friend, who was caretaker of the property, initially said Watson arrived between 10am and midday.

Water-taxi driver Guy Wallace (seen here at Furneaux Lodge) delivered Ben and Olivia to a mystery yacht with a mystery man. At trial, Wallace agreed Scott Watson was most likely the mystery man, but since then has been adamant he was wrong, saying he was pressured and tricked by police into this identification.

Watson says he and the caretaker went up the creek at the back of the property to do something to the water intake, and would have also taken a look at the caretaker’s cannabis patch.

“It was sort of a perfect little spot to grow dope in, too. North facing, flat, there was a little road. I don’t think he grew very good dope – from what I saw, it wasn’t.” Watson admits he’d smoked some of the caretaker’s cannabis, but swears he wasn’t in business with him. When police searched the property, they found more than 200 plants, for which the caretaker was later convicted.

Watson describes the caretaker as “a nice guy”, but believes police used the cannabis charges to lean heavily on him. Eventually the caretaker altered his estimation of Watson’s arrival to after 5pm, better fitting the police scenario that Watson had been out to Cook Strait to dump Ben and Olivia’s bodies, before arriving at Erie Bay. The caretaker later claimed police had tried to turn him against Watson, alleging it was Watson who dobbed him in over his dope growing. “It was just a load of garbage,” Watson insists. Watson says he hung out with the caretaker and his children that day, shifted his boat from the wharf out to anchor, and recalls cutting his foot on the beach at some stage. He thinks it was the following day that he repainted Blade’s cabin sides with the paint the caretaker had provided.

After three days at Erie Bay, Watson headed back to Picton, then went sailing again with his sister, Sandy. It was around this time he first learnt Ben and Olivia were missing – he recalls flyers in shops and something being on the radio. On January 7, having heard that police wanted to speak to anyone who’d been at Furneaux Lodge, he voluntarily went to the Picton police station and pointed out where Blade had been moored. The following day, he made a statement to the police and on January 12, they asked to speak to him again.

Until this interview, Watson maintains, he had no idea he was even a suspect. In fact, he was already the prime suspect, shown by the fact police seized his yacht while he was being interviewed, and raided the homes of his parents and sister.

Police described Watson as agitated, aggressive and evasive during the interview. Watson says he was just pissed off police were disrupting his day by dragging him in for several more hours of questioning. Though he never interviewed him, investigation head Detective Inspector Rob Pope later claimed Watson was “shaking and looking quite emotional” and on several occasions appeared as if he was about to say something “and then just up go the shutters”.

“Well, he’d write that, wouldn’t he?” scoffs Watson. “It’s not true. It’s a little white lie for him to tell amongst all the other sea of lies.” The interviewing officer was actually Detective Tom Fitzgerald, and Watson says Fitzgerald’s jobsheet “basically makes out he’s Mr Wonderful and I’m Captain Caveman”. He remembers Fitzgerald at one point walking around the room and deliberately banging into the arm of his chair. “For me, that was one of the moments I just thought, ‘You pack of arseholes, what are you up to?’ I’d had dealings with policemen before. But not like this.” However, he was reassured he was being interviewed only as a witness, not a suspect, and it wasn’t until he’d actually signed his statement that Watson realised police had an entirely different view of him. “More than anything, when basically Tom Fitzgerald said, ‘What have you done with these people? Where are they?’ That’s when it really sunk home.” Fitzgerald then told Watson his boat had been seized.

“I’m not sure if I’m shitting myself, I was just like, ‘What the fuck?’”Before he was allowed to leave, police took further photos of Watson. He remembers the photographer pushing the camera close to his face and in one shot, Watson is caught midway through a blink. Conveniently, this fitted a description from some witnesses of a man at Furneaux Lodge with droopy eyes. Police later used this in a montage from which a key witness identified him. As Watson says of the unnatural photo: “It was the best photo in the world for them.” Still disbelieving that Blade had been taken by police for examination, soon after he left the police station Watson went to Shakespeare Bay, where it had been moored. “Coz I thought, these guys are talking rubbish, they must be taking the piss. It’s like if you’ve been told a tornado’s taken your house, you think, ‘What the fuck? I need to go and check on this.’ You need to believe it with your own eyes.” But sure enough, Blade was gone, hauled out of the water and trucked to a nearby Air Force base for forensic testing. That night, Watson met with a lawyer. “And he said, ‘The policeman is not your friend.’ I always remember those words – the policeman is not your friend.”

Just why police isolated Watson so early in the investigation as their number one suspect has never been clear. Rob Pope says it was a gut feeling – that Watson had “the right sort of agenda and pedigree”; that he began to “stick out like dogs’ balls” – without ever specifying any evidence that connected Watson with Ben and Olivia’s disappearance.

“I think it was because I had a criminal record,” suggests Watson, “and I was [at Furneaux] alone and I left alone. I told them that. Basically I was an easy target for them. I was the easiest person that they could pick.” Watson’s criminal record – extending to 48 convictions – is frequently presented as a reason he is likely to be guilty of murdering Ben and Olivia. The fact that all but one of these convictions were from when he was aged 15 to 18 – eight years before Ben and Olivia disappeared – is usually ignored. The fact none were for sexual offences and only one involved any degree of violence is also generally missing.

Watson had been kicked out of college in Ashburton at 14, having given staff every opportunity to get rid of him. “I didn’t want to be there, didn’t want to be at school.” He drifted between Ashburton and Christchurch, gradually getting into trouble. “I was no angel. But I never did anything major. I think I’ve got one assault charge, from when I was 16 years old. Common assault. It was me and another 16-year-old having a fight outside a pub – I think it was listening to the band at Fat Sally’s in Christchurch – out on the street. “I was an over-exuberant bloody boisterous teenager who got into trouble as a juvenile. Just a wee shit. Just basically a little shit. I wasn’t mugging anyone. I stole a couple of cars, got caught with some weed, some pot, got wasted, got drunk, couple of burglaries. And everything that did happen was basically because I’d been wasted – drunk, stoned. And then I got over it and got on with life. You grow up, you get a job.

“I was a 16-year-old stoned kid. Some people end up like that. But a lot of guys I hung out with have gone on to become successful and all the rest of it. Because a kid decides he’s going to get stoned when he’s 15, 16, 17, doesn’t mean to say he’s a fuck-up for the rest of his life.” Watson was sentenced to corrective training just after he turned 16 and later served two short jail sentences. “The only reason they put me in prison was because I didn’t go and do their periodic detention or community service. If I’d gone and dug ditches for six months every Saturday, I suppose I wouldn’t have been in jail. But yeah, I had other things to do. But you think back now – you make dumb decisions when you’re a teenager.” His only other conviction before Ben and Olivia went missing was from May 1995, when he discovered someone stealing his dinghy in Picton. “I just said, ‘Hey, that’s my boat – I want you to put it back.’ And he’s one of the local rednecks in his four-wheel-drive – gets out and you think, ‘Oh, here we go, you’re going to get your head kicked in in the middle of the night.’”

So Watson pulled a marlinspike from his pocket – a 10cm sharpened spike he used at the boatbuilding yard where he worked – and the guy gave back his dinghy, but Watson was charged with possessing an offensive weapon. He’s still unsure why Picton cops immediately fingered him as a likely suspect in the disappearance of Olivia Hope and Ben Smart, even before Rob Pope arrived to take over the investigation on January 6, 1998. He’d once thrown an egg at a guy on his boat near the ferry terminal and had a cop tell him to leave the area. “And I’ve grown a bit of dope in the Sounds. So has every other young guy in Picton. It’s what we do. I never got caught, but me dope got caught. And I knew I’d been watched by the police.” His dope growing was a hobby, he says, about 20 plants a season, for his own use. “Some people get a pound of dope off a plant. But my plants were never any good.”

The police didn’t arrest Watson until June 15, 1998. That was six months after his yacht had been seized and in that time, everyone knew that he was the prime suspect, ensuring his notoriety.

But equally damaging was the gossip about Watson’s family and attempts made to ostracise them from the community. The worst of the rumours was that Watson was sleeping with his sister. Police deny any role in starting or encouraging these rumours, but even Olivia Hope’s father, Gerald, says they constantly fed his family stories about how bad the Watsons were. “To get their interception warrants,” says Watson, “that Rob Pope character basically makes out that my family are some sort of gangsters – like the West family from Outrageous Fortune. The way they were portraying us was just absolute garbage. And they were doing this all round, and the locals sort of got their backs up about the whole thing. A lot of people said, ‘What the hell are you talking about? Leave them alone, they’re just normal people.’”

Until his arrest, the media were free to link him with Ben and Olivia’s disappearance, without fear of jeopardising a trial. “At the time, I was – what’s the word for it? – just pretty numb about the whole thing. You can’t believe that this sort of thing is going on. They stick you on TV every night saying you’re a super arsehole.” Neither Watson nor his family spoke publicly during this period, meaning the media relied on comment from the police and the victims’ families, with little leavening. But Watson doubts it would have made any difference. “None of us had a degree in media studies. The police had a boardroom full of people deciding, like, this is war. And we basically had a lawyer we could afford. And they just had unlimited resources.” The close relationship between the media and the police was exemplified by the open affair conducted between an officer and a reporter. “The media sold their arses to the cops. And the cops used the media like the media was a whore. That’s the most bitter way of me putting it. I just wish the media weren’t so fucking stupid at the time.

“You worked for the Marlborough Express. How do you feel about that? I don’t want to come here and insult you or anything – but you were there stirring up a lynch mob. You were carrying one of the torches.” Watson says the whole community was seized by Ben and Olivia’s disappearance and urgently wanted someone to blame – so the police, under huge pressure to appease this public demand, created a case against him. “They manufactured their own evidence. They manufactured this image through the media that somehow I was it. What they did first was they told a little lie, right from the beginning. And then they’ve got to lie for the next one and then lie for the next one and it becomes a situation where they can’t ever go back on what they’ve first started doing. But they had the media there and you guys were believing it and printing it. They created their own momentum. They dragged my boat through the main street of Picton – they had to get a conviction.”

Every comment he’d made was reinterpreted to sound sinister, every action he’d taken was twisted to seem suspicious. “There was just a lot of creative writing going on. They stirred people up to imagine these things. Every blade of grass has a shadow and a bogeyman behind it.” That “creative writing” extended to his eventual arrest, early one winter morning near Christchurch. “This is something that’s always got under my skin. I was at my brother’s place and Tom Fitzgerald has always said that when he first arrested me, I said, ‘About time.’ That’s a load of garbage. That’s just a load of shit. Never said it. He made it up. That was his little moment of glory. If you were just getting arrested for murder, would you say something like that? He was just trying to put the icing on the cream bun. Just a load of rubbish.

“At the end of the day, these people are only focused on one thing and that’s, ‘Right, we need to get this guy convicted – we need to demonise him in the public.’ That’s their process.”

By the time of Watson’s trial at the High Court at Wellington in June 1999, that demonisation was almost complete, he felt. Ben and Olivia and all the events of that New Year’s Eve party had become part of common culture over the previous 18 months. And Watson’s alleged part in snuffing out two young lives was equally well known. “Before they arrested me, they spent the first six months just bombarding – boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, he’s this, he’s that, and everything else. And that was just the warm-up for the jury.”

On the second day of the three-month trial, Watson remembers a Crown prosecutor referring to Tamarack, the yacht Olivia had sailed to Furneaux on. At the mention of the name, Watson says, one juror shot him an “I’ll kill you” look. “Just from hearing one word. And they hadn’t heard any evidence.” With nearly 500 witnesses, Watson says the jury was swamped with often irrelevant evidence, and some were there simply to denigrate him. “Basically to say something horrible. The prosecutor would lead them out, saying, ‘And you knew Scott Watson?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘How do you know Scott Watson?’ ‘I think he stole something off me,’ or ‘I had a fight with him at the pub,’ or ‘Oooh, he looked at me, looked at my partner.’ They just character-assassinated me. They made the jury hate me.” He recalls one witness claiming he’d said something about killing women and to “watch the papers”. “I never said anything like that. And it might not be taken as gospel, but put it all together and it just creates a feeling.”

Watson says he himself fell into the same trap when watching coverage of another high-profile trial, when Ewen Macdonald was accused of murdering his brother-in-law, Scott Guy.“In about the second week, I thought, ‘You dirty bastard, you’ve done this, it’s fucking obvious.’ But then I checked myself and thought, ‘Well, hang about, they haven’t actually said anything or given any evidence that you’ve actually done anything.’ I was shocked that I would be so judgmental. They were just convicting this guy on getting people to hate him – it was exactly the same thing that happened to me.” Watson admits he frequently didn’t understand the legal machinations of the trial, but has nothing but praise for his trial lawyers, Bruce Davidson, who’s now a district court judge, and Mike Antunovic. “Bruce is a brilliant lawyer. And he said everything at my trial that needed to be said. But he was dealing against this [Paul] Davison QC character and [Kieran] Raftery and [Nicola] Crutchley, who was deputy solicitor-general. After hearing what they said in court, I reckoned they were three of New Zealand’s biggest bullshit artists.”

Scott Watson (right) and his lawyer, Kerry Cook, in the High Court at Christchurch, 2015.

Every morning during the first weeks of the trial, the Crown lawyers would deliver a large bundle of new evidence to Watson’s lawyers, leaving the defence scrambling to sift through it and investigate its relevance. “That’s what my lawyers were up against. The truth doesn’t come into it – it’s what they [the Crown] can get away with. It was a prison guard who actually said to me, ‘A court case is never about the truth, it’s just what they say on the day.’ “What people need to understand is that people lie. They can just garbage their way through everything – and it’s acceptable. The only thing missing the whole time was the soundtrack to Jaws. When the policeman got on the stand, they were playing ‘Eye of the Tiger’, the theme to Rocky. Honestly, it was like a movie how they played it out.” Despite this, when the jury returned with its verdict, Watson was convinced he’d be walking out a free man. “Yeah, of course. You know the person you are and what you have and haven’t done. There’s a lot of stuff taken out of context through the trial, but you think, are these people smart enough to see through the garbage?”

Even the crucial evidence about two of Olivia’s hairs supposedly being found on a blanket on his yacht was surrounded by so much doubt Watson was sure the jurors would seriously question it. “But the trial took so long they forgot about things like that.”

His lawyers were equally confident the jury would acquit him and had brought wine to celebrate, and his prison guards had a new set of clothes for him to change into. But when the foreman was asked to deliver the jury’s verdict, he pronounced Watson guilty on both murder charges. “Just, pooosh. Just devastated. But in front of all these people, you’re not going to flip out or anything, are you, or collapse? I think it hit me more when I went downstairs [to a cell], actually.” Watson couldn’t help himself, though, telling the jury, “You’re wrong,” before he left. He’d still say the same now, but doesn’t hold them responsible. “Nah, they were bullshitted. I just think they were people, I think they were just bloody people. Back then, I probably was more angry. I don’t have a festering hate going on for them. But I often think, why couldn’t you have thought a bit better?”

He asks those jurors to at least look at what happened and if they now have doubts, say something publicly. “Look at what else has come out since the trial – the real facts – and what you were told in court. You were lied to, they lied to you. But depending on what sort of people they are, they won’t believe you, or they won’t even look at [the new evidence]. Because I’ve thought in the past, how many of them watched that documentary Keith Hunter did? [Murder on the Blade?] “I’m sure they must have all watched it. And what did they think? Or do they think, ‘Oh, it’s just TV, they must be lying.’ It’s human nature; you don’t want to admit you’re wrong.”

So why has it taken 18 years for Scott Watson to speak publicly? Why now? Why not when he had the chance, back at his trial in 1999? “Because my lawyers said not to. They thought I didn’t need to, obviously. I wanted to get up there and say my piece. But if I had taken the stand, I probably would have been convicted as well. Because I think [prosecutor Paul] Davison would have done me. If I’d have said the word ‘fuck’ it would’ve been drawn out 87 times. I wouldn’t have been able to out-talk Davison, coz he would’ve been talking me into some little corner and I would’ve said, ‘Oh, piss off, mate, you’re making it up as you go along.’

“I’m not the most eloquent speaking person. At some stage I would’ve, not flipped out or anything, but just said, ‘Whatever, mate.’ And you come across as a bad person. And that’s the part of it – he didn’t need to prove anything in court, just make out that I’m a bad person to the jury.” Likewise, the defence didn’t call Watson’s sister, Sandy, who’d been sailing with him before and after New Year. “She would’ve told [the prosecution] to get fucked. They would’ve demonised her. They would’ve done it in front of the jury and that’s where it all mattered.” Many times throughout the trial, Watson says, he wanted to respond to witnesses who he felt were inventing things or deliberately slurring him. And many times since, he’s wished he’d spoken in court to defend himself. “Yeah, of course. Ooh, yeah. But at the time it was so confusing as well. This is a big monster – what’s going on here?”

Watson says he’s always been prepared to defend himself, right back to when police seized his boat and Gerald Hope said he wanted to talk to the yacht’s owner. “As a person, I would have done that. On the night I went and saw our lawyer, I said, ‘Well, this guy says he wants to talk to me.’ I said, ‘Right, I’ll go and talk to him.’ And the lawyer said, ‘No, whatever you do, do not talk to him. And don’t talk to the media.’ That was his advice and you’d be a stupid fool not to take his advice.”

Over the years, while his case has continued to be publicly dissected, Watson says he’s been tempted many, many times to put his side of things. He’s often thought of writing to newspapers, but has believed that he wasn’t permitted to. “And I’m not allowed to talk to the media. Until Kerry [Cook] came along, none of my lawyers have wanted me to do it. And it’s basically taken since my association with Kerry to actually get it to happen. It’s taken years. It’s just an uphill battle. Basically you’ve been fighting another arm of the police department.” (See The Battle to Interview Scott Watson, on page 48.)

But after 18 years, why should the public believe him, believe what he’s finally saying? “It’s the truth. I’ve got nothing to hide, but I’ve also got nothing to lose. Worst-case scenario, I’ve resigned myself to the fact they’re going to do their darndest to keep me in jail forever. And something needs to be said.”

Nothing to hide. Of course, the police, prosecution and jury all believed Watson had plenty to hide and did his very best to deceive investigators. And in relation to criticisms of the police case against Watson, Rob Pope has also claimed there are no secrets.

“There’s nothing to hide about this investigation. If anything, it’s probably one of the most publicly trawled investigations in recent times.” Pope has always insisted that police followed proper process, all evidence was tested in court, and critics are misguided. Here are the crucial elements of the case against Watson and his responses:

Extensive Cleaning of Blade

The Crown alleged the interior of Watson’s boat had been thoroughly cleaned, and even cassette tapes and their covers had been wiped. The suggestion was that he had tried to remove any evidence of Ben and Olivia being on board. “Their expert stood up in court and said it was just normal.” (An ESR scientist testified only 30-50 per cent of hard surfaces had actually been wiped down, and only half the cassettes.) What many people forget is that Blade was Watson’s home. He says he’d cleaned the interior after a particularly rough trip from Tauranga to Picton, just before Christmas 1997. “It took ages. We got to Cook Strait, the entrance to it, and the wind came up so strong we actually had to take down all the sails and we ended up getting blown back, sort of up the coast. In a little boat, it’s a big deal. And out at sea you get continually whoosh, whoosh, whoosh, hours and hours and days and days of pounding. You get spray flying round in the wind and it all just gets everywhere. And you clean your boat. You’ve got a small space, you clean it. You don’t live in festering damp – you clean things. I’m sure if someone goes away in a caravan, they’ll clean it.”

And the cassettes?

“Just gave them a wipe, with a damp cloth, and I would’ve done it with my stereo and the face of the electronics on the boat, everywhere. Anything that can handle a wipe. Lights, everything. A cassette on a boat dies coz of the salt. That’s how they crapped out. You got salt everywhere, especially if you’re in a small boat and you sail down the coast. You get thrown around, you’ve got water going everywhere. If you wipe the tape, why wouldn’t you wipe the inside and outside of the cover? It was obviously a crime that a guy cleaned his boat.”

Rub Marks on the Hull

When Blade was pulled from the water, observers noted an area of the hull near the stern where weed had been rubbed off. Suggestions arose that Watson had wrapped Ben and Olivia’s bodies in a sail or some other shroud and dumped them overboard, and they’d somehow rubbed against the hull in the process.

Weed growing on a yacht’s hull creates drag and slows it down. Watson says Blade was due to be slipped to clean and paint the hull in the next month. In the meantime, he cleaned some of the weed around the propeller to try to get a little more speed, as he travelled around the Sounds. He remembers jumping overboard with a scrubbing brush while anchored in the Sounds some time around New Year. The reason he cleaned at the stern was that there were things around the waterline to hang onto with one hand – the rudder and propeller – while scrubbing with the other. Elsewhere on the hull there was only the edge of the deck to grip, making it almost impossible to clean very far below the waterline.

“These bodies, that are supposedly weighted down, but floating all around the propeller of the boat? Why would someone dump something round the propeller? It’s just a nonsense. But people believed it. Well, a jury believed it.”

Missing Anchors

After Watson’s yacht was seized, rumours began swirling that the boat’s anchors were missing. Again, the suggestion was that these had been used to weigh down the bodies when they were dumped at sea. Police refused to comment on this, allowing the rumours to gain currency. However, police were well aware there were three anchors on board. Nor was there any evidence any anchor chain was missing.

“It was something like you’d see on SpongeBob SquarePants, or the movies. It’s on people’s brains, it creates their own documentary. What better to say than, ‘There’s bodies weighted down with the anchor.’”

Hatch Scratches

Even more evocative was the interpretation given to scratch marks on the foam rubber inside Blade’s forward hatch cover. The Crown contended these were made by fingernails and the picture created was of a trapped Olivia desperately clawing the hatch to try to escape from Watson. Watson’s explanation for the scratches is more mundane.

To prop up the hatch cover and allow air to circulate, he had a small wooden stick that he kept in a groove that ran around the hatch opening. Before New Year, he had taken his sister and her two daughters sailing. The hatch was open, the girls found the stick and began scratching the foam.

“And the scratches went to the very edge – where you can’t reach when it’s closed. It can’t be done while the hatch is shut. And you couldn’t have locked the hatch from the outside – or the inside. You can tie it from the inside, but that’s all. The only way it can be secured from the inside isn’t with a padlock or anything, but with a piece of string.”

Arguably he could have lashed something over the hatch from the outside to keep it closed. “But what would I put on the top. What have I got to put on top of it?” Moreover, the image of Olivia being trapped in the forward compartment begins to lose credibility when you realise there is no door on the compartment – it’s open to the rest of the yacht’s interior. And therein lay a host of weapons or things that might have been more use to escape than scratching at the hatch cover.

“There’s a speargun sitting there. In the galley, there’s a million knives. Under my chart table, there was an old machete. I think there was an axe there, too. There was my tool locker that was basically right there that had every tool you could come up with. There was an old rusty slug gun in the toilet. There were flares there. The whole thing’s ridiculous.

“What was that movie? Dead Calm – have you seen Dead Calm? That’s what people saw. They saw Nicole Kidman. In a boat. With a maniac. Scratching at this steel goddam hatch.”

Repainting Blade’s Cabin

Police claimed Watson’s painting the cabin sides on Blade was an attempt to disguise his boat. Several weeks earlier, when visiting the caretaker, Watson had talked about painting Blade and the caretaker mentioned there was some spare paint in his boatshed that Watson could have. “And he actually said, ‘Your cabin sides would look good blue.’ I always thought it looked really nice red. But he kept on going on how nice it would look blue. And he had some blue paint there. So I said brilliant.” Even better, the caretaker’s paint was chlorinated rubber, which was hard wearing and didn’t require lots of preparation before being applied. “You don’t have to sand things. Who wants to sand? I’ve done enough sanding.”

The Wind Vane

The other thing police suggested Watson did to alter his boat’s appearance was remove a self-steering wind vane from Blade and “hide” it inside. Watson finds this interpretation laughable. Sailing in the Sounds is fluky, with gusty winds coming out of the many bays, and so he spent most of his time motoring. The second-hand self-steering mechanism was already worn and rattled and was only likely to be damaged if left up. Given he wasn’t going to be using it, he simply removed it after New Year, as the manufacturer recommended, and stored it down below, where there was room.

Changing His Appearance

Many witnesses described a mystery man at Furneaux Lodge who was unshaven and had medium to long hair. Watson was clean-shaven and had short hair. Police suggested to some witnesses that Watson could have had a haircut or cleaned himself up in the interim. “But I hadn’t had a haircut. I went up to [a friend who had been at Furneaux Lodge with him on New Year’s Eve] and said, ‘Hey, buddy, have I had a haircut?’ And he said no, you haven’t. And I remember [his wife] had a camera there to take a photo of me.”Watson doesn’t know what happened to the photos. However, other photos of him at Furneaux Lodge confirm he was clean-shaven, with short hair.

Missing Clothes

Police have always claimed the blue denim shirt Watson wore on New Year’s Eve was never found. Watson insists all the clothes he wore that night would have been on his boat. He would have taken them ashore, to his parents’ house, to wash them, but by January 12, when Blade was seized, they would have been back on board and found by the police. “I guarantee it. Guarantee. They were there. The clothes were there.” The curious thing, Watson says, is that when police raided the homes of his parents, sister and brother, there were denim shirts there that weren’t taken to check. If police had been truly interested in finding denim shirts, they would have removed these, he argues. “It was just another little slant on the truth – just a big fable.”

Holes in the Squabs

Examination of Blade found holes cut out of two foam squabs. The police suggested Watson had dug out bloodstains from these areas – and added to the disturbing picture by mentioning Olivia had her period at the time. “The one in the front was from a cigarette,” Watson explains. “I fell asleep and I ended up burning my hand. And the one at the back was from me spilling paint all over it – it was that chlorinated rubber paint. The paint soaked in and had gone rock hard.” Police also said Watson had reversed the squab cover in the front berth to hide the hole. “I was probably getting it away from where you sleep, that’s all. You don’t want to sleep right where there’s a hole. But I don’t actually remember doing that.”

Hairs on the Tiger Blanket

Also in the front berth where Watson slept was a tiger-patterned blanket. ESR scientists recovered nearly 400 hairs from it, mainly short and dark. An initial examination of the hairs revealed nothing similar to Olivia’s blonde hair. However, on a second examination, a few weeks later, an ESR scientist found a 15cm strand and a 25cm strand of blonde hair, which she’d not noticed previously. These hairs were later shown to have very likely come from Olivia. Complicating the curious fact the scientist hadn’t found the strands beforehand was that on the second examination, she looked at them on the same day and on the same laboratory table as reference hairs taken from Olivia’s home, raising questions of contamination. Further mystery was added by an unexplained slit in the bag containing the reference hairs. Because police hadn’t counted how many reference hairs were taken from Olivia’s home, it was impossible to say if any were missing.

Watson is adamant the two blonde strands weren’t originally in the bag of hairs taken from the tiger blanket. “She wouldn’t have missed them. There’s no way. Even a person without a magnifying glass in front of them and a lab jacket on and a pair of tweezers wouldn’t have missed them. And suddenly she’s told to go and look again and suddenly they are there.” He also questions why police needed to take reference hairs, well before anything was recovered from the tiger blanket. In his mind, there is no doubt the hairs were deliberately planted, to shore up an investigation that had found nothing incriminating against him.

Secret Witnesses

The case against Watson was entirely circumstantial. No bodies had been found, there were no eye-witnesses, and other than the two hair strands allegedly found on the tiger blanket, there was no evidence Watson had ever been with Ben and Olivia. But a month after he was arrested, two prisoners came forward claiming that while he was on remand, Watson had admitted killing the young friends. These jailhouse snitches gave emotive testimony at trial about Watson’s descriptions of the murders. “I was supposed to have made a confession to a guy through a peephole this big,” Watson says, holding his fingers in a circle about 5cm across. “Some guy I’d never met? And people had constantly been saying to me, be careful who you talk to. Every day. My father or family or lawyer – ‘Don’t talk to anyone.’”

The drama involved with the snitches’ testimony – the court was cleared except for the Hope, Smart and Watson families, and even the windows were blacked out – must have persuaded the jury to overlook the sham of admitting such illogical evidence, Watson says. “It creates a feeling – ‘Ah, Watson’s talking to these people; he’s obviously associating with these people.’” Scott Watson’s cell is unlocked at 7am. He can have breakfast in his cell but usually goes to the dining room for some toast. At Rolleston Prison, they’re fixing up old houses on site, teaching the inmates new skills. Watson has been plastering lately. They work a normal day, with dinner about 5pm. When he was in the main prison, it used to be 3pm.

The evenings are free. He plays cards, goes to the gym, paints. He began painting in Paremoremo, had to fight to get art supplies, but recently one of his paintings sold for $1200. It was of a boat.

“I used to read a bit, but I’ve just got sick of reading. You end up reading the whole library. You end up having to read books twice or three times because there’s nothing really else to read.”

He writes a lot – letters mainly. And he feeds the cats that hang around the prison. “The funny thing is, a stray cat on the most freezing-cold night, starving, will not eat the meat out of a prison pie.” His partner, Christina, now has a couple of the prison kittens.

For years, he was locked up 22 hours a day. Boredom is a constant enemy, so you have to find things to do, Watson says. “I live on a different planet to you, to the average person out there. It’s a different mentality. You’re institutionalised after 18 months.” You become numbed, automated, dulled by routine, he says. “But that’s the way Corrections wants it.”

Watson’s father, Chris, has fought tirelessly for his son’s freedom, as have the rest of his family. “But that’s how it should be,” says Scott Watson.

He doesn’t get a lot of visitors. Christina is allowed to see him once a month for three hours. They knew each other as kids when they were both living on the West Coast. When Watson got shifted from Paremoremo to Christchurch, about 11 years ago, Christina contacted him and has visited ever since. Watson’s dad, Chris, travels down from Picton every month, and they talk by phone a couple of times a week, and his sister Sandy phones often, too. Nobody in his family has ever given up fighting for him. “But that’s how it should be.”

When his mum, Beverly, died of leukaemia in 2012, Corrections refused to let him out to attend her funeral. “Your mum’s just died and you think, ‘You pack of mongrels – what are you doing?’ They weren’t doing it for anything to do with regulations.” Rolleston Prison staff were happy with a plan to get him there and back securely, but it was overridden by head office in Wellington. The irony was Watson had been working in the community for months, on a logging gang, with minimal supervision – and no problems. Yet even a plan to have him taken in handcuffs to the funeral chapel was deemed unacceptable to the powers-that-be. Watson reckons you can’t get much lower than that.

It took an urgent judicial review in the High Court by Kerry Cook the day before the funeral to get the decision overturned, and for Watson to be allowed to attend.

What happened after January 1, 1998, swallowed his parents, Watson says. “Yeah, well, it swallowed all our lives. I get told a lot of things, but I’m not there to see it. But they just had their lives taken away, basically. I don’t know if that’s what killed Mum – I can’t say it did – but of course it couldn’t have helped.”

He was always treated as a high-profile inmate by jail authorities and has also attracted attention from other prisoners. “Well, they try it on. Hell, yeah, they try it on. It’s just the way it is. You’re in prison, you’re in a combative environment. There’s a whole bunch of angry people around you. You’ve got to survive. And if you don’t back up on it, you’ll lose your shoes, you’ll lose your watch, lose your clothes, you lose your lunch, you lose your dinner.

“Yeah, I’ve been in fights and things, yeah. I’ve never really picked a fight, but altercations just happen.” He got done for an assault one time, but reckons the other guy was coming at him and that he punched him in self-defence. And then there was the well-publicised story he’d sent lewd photos to a 15-year-old. The accusations were false – the photos were from a prison Watson wasn’t in. However, he does admit having a cellphone at one stage. A woman sent him provocative photos; he replied in kind. When word got out, he handed in the phone to avoid everyone’s cells being ransacked.

Watson acknowledges he’s not always been a compliant prisoner – aggrieved and angry about being found guilty of something he didn’t do. “It comes from being locked in a little cell. Having someone who obviously thinks they’re better than you – and they’re just a prison guard – who comes along and pokes and prods and looks at your arsehole, goes through all your stuff, pulls it all apart, throws it on the floor. I found the best way to deal with cell searches was when you know one was going to happen, you take everything in your cell and dump it all on the floor, tip it out. Coz you’re actually better off that way coz they’re going to come and do that, anyway. It’s demeaning, it’s dehumanising.

“And then you get prison guards saying, ‘Oh, you’re never going to get out of here, Watson, you’re going to stay here forever.’ Until about 2011, I sort of just hated them. I just didn’t want to play their stupid games. If there was something to complain about, I’d complain.” Since he’s been at Rolleston, in a lower-security unit, his attitude has changed somewhat. “The feeling of injustice is still there, but the thing is, you just can’t be angry, otherwise you get really, really twisted up. If you’re going to be angry, you walk around angry. If I walk around angry all day, I’ll be back up to Auckland, maximum security.”

Even by speaking out in this interview, Watson fears Corrections will send him to another prison. “I’m following all their rules, all their things, going to the Parole Board, not getting put on charge for things – you’d think they’d leave you alone. But in saying that, they can just come up with any excuse, any reason. They just manipulate things to how they want it.”

Watson talks in snatches of sentences. Often he gets three-quarters of the way through them and then runs out of words, runs out of ways to express what he wants. You can sense it’s all there inside him, but it snags somewhere in his throat and regularly just ends with a shrug of his shoulders. His answers frequently begin with, “Of course.” As if what you’re suggesting happened to him and how come he’s still in jail is so obvious. That bitter certainty of fate. “Like I say, I’m not the most eloquent speaking person – and 18 years in here hasn’t helped that.” North & South’s interviews with Watson were held over three days, and totalled nearly seven hours. Even in that time, it’s never possible to ask everything about the case, cover everything that’s occurred since New Year’s Day, 1998.

“I’ll probably go away and think of a million other things I want to say,” Watson said towards the end of the final interview. “While you sit there at night, you think of all these things.”

Despite what he says about not remaining angry, there’s bitterness about what’s happened to him, about the people who lined him up, maligned him, and convinced a jury he killed Ben and Olivia.

He labels the cops who investigated him a bunch of crooks who’ll never back down on their claims he’s guilty. “No, coz that’s their reputations. They built their reputations on me. If they weren’t cops, they would’ve probably been robbers. They lied and manipulated from day one. The Blenheim crowd called in the Christchurch boys – ‘Right, let’s get someone for this.’ And they were just twisting and reconstructing the truth.”

When the investigation’s second-in-charge, Detective Senior Sergeant John Rae, retired in 2014, he said Watson should never be allowed out of jail. Despite having never spoken to him, Rae claimed Watson was a psychopath who could easily murder again.

“The only reason he’s speaking like that,” says Watson, “was because he still knows that probably in the future I’m going to get the conviction overturned. And this is just another, ‘Oh, he’s guilty, don’t trust this guy, he’s bad, he’s bad.’ It’s just him trying to reconvict me, or trying to strengthen their conviction again, because he’s got fears that what he’s done or what his mates did is going to come back and bite them in the arse.”

But beyond the cops and lawyers and judges who he believes have all had it in for him, Watson remains surprisingly equable about those who were part of the case against him, including key witnesses. “The thing is, I don’t blame anyone. People got primed up. They got bullshitted to. Like the media – you got lied to. And in the naivety of the New Zealand culture, the policeman’s a nice guy – always talk to a policeman, he’s great, trust him.”

At Watson’s trial, perhaps the most important witness was Guy Wallace, the water-taxi driver who’d delivered Ben and Olivia to a mystery yacht with a mystery man. Wallace described this person in detail, and little of this matched Watson. He was shown photos of Watson and said this wasn’t the person on the Naiad with Ben and Olivia. But much later, when shown the “blink” photo of Watson, he said Watson resembled the mystery man. And at trial, he said he was “pretty definite” Watson was the man on the Naiad, though he acknowledged there were a number of differences between Watson and the man who disembarked with Ben and Olivia.

However, since Watson’s conviction, Wallace has repeatedly stated Watson wasn’t the right man and that he had been pressured and deceived by police to identify him.

Despite Wallace’s “identification” being utterly crucial to the Crown case, Watson holds no animosity towards him. “No, not at all. Because I know what they would have done to him. I read the transcripts of what they did to him [in police interviews] and then the statements he made and you just know what got put on the guy. [Tom Fitzgerald] is not just interviewing him, he’s actually doing him.”

Watson admires Wallace for sticking to his position for so long, and then having the courage to admit he’d wrongly identified Watson.“The thing is, the average Joe Bloggs would’ve just given up, actually. The average person would’ve just folded way back and said exactly what the police wanted him to say.” Of course, Wallace isn’t the only person to have changed their views and testimony since the trial. Another crucial witness, Furneaux Lodge barwoman Roz McNeilly, has equally retracted her identification of Watson, saying the police tricked her.

One of the secret jailhouse witnesses has recanted his claims. And then there’s Olivia’s father, Gerald Hope, who has voiced numerous concerns about the police investigation and the trial, saying that while they got a conviction, they never got the truth.

When Blade was seized and Hope said he wanted to speak to its owner, Watson wanted to tell him, “It wasn’t me. I don’t know where your family are – don’t know anything about it.’”

Watson says he’d still be happy to speak to Hope, as long as he could be sure Hope was genuine. Given what’s happened to him, Watson trusts few people. And the fact Hope opposed Watson speaking to North & South unless he was present, and opposed Watson’s first bid for parole, has made him cautious about Hope’s motivation. “It made me worry that he was going to come in and see me and no matter what I said to him, he was going to walk out the gate and he was going to say, ‘I’ve looked the devil in the eye. I know he’s done it – I’ve seen him.’ And there’d be drama and lights, as seems to go with Gerald. I’m not rubbishing him – I’m just pointing out what I’ve seen and how I’ve obviously come to know Gerald Hope.

“I feel for the guy, for what’s happened in his life. But that didn’t have anything to do with me. And at this stage, they’ve kept me in prison for 18 years for something I haven’t done and, yeah, they’ve destroyed my life. They’ve basically murdered me. That’s what’s gone on. I’m in jail. They’ve killed me. The system’s destroyed my life, but I see the system has manipulated Gerald as well, to make him believe anything that comes out of their mouths.

“Gerald’s said he’ll help me if he believes me, but these people that hold all the keys, they’ll ignore what he has to say – just as much as Keith Hunter’s book [Trial by Trickery], documentaries, maybe even this story. Hey, I hope it helps, I think it might do. But can you see them coming along and saying, ‘Sorry, we screwed up’? Can you actually ever see that? Gerald doesn’t realise what he’s up against, doesn’t realise the machine.”

Watson also points to the obvious: if Hope accepts Watson didn’t murder his daughter, then it means the real killer is still out there, but the chance to catch him – and maybe save Olivia and Ben – was lost when the police focused on the wrong man.

“If he changes his mind, it’s almost like a catch-22 situation. By changing his mind, he’s actually got to give up on a resolution for his daughter and then he’s back to, ‘I don’t know.’ And isn’t it better for him to feel that he does know? He probably goes backwards and forwards all the time – but when he goes back, then he’s got no closure or certainty. There’s no comfort, there’s no solace.”

It’s something Gerald Hope has talked about – the “what if” scenarios that flood his mind when he wakes up, that he has to push aside, for the sake of peace.

“But it doesn’t hurt as much as waking up next to a concrete wall every morning,” says Watson quietly, “and for a split second wondering, ‘Where the fuck am I?’ And then it dawns on you. ‘Where the hell am I? How the hell did I get here?’ And you know you can’t get out.”

Equally, Watson would be prepared to meet Olivia’s mother, Jan Hope, and Ben’s mother, Mary Smart. (Ben’s father, John, died in 2009.)

“Yeah, if they want to. But are they going to believe me after all this time? I’m sorry for their loss, but it wasn’t me. I’d really like them to just talk to someone that hasn’t believed all the bullshit. It’s like a pyramid, you know. If nothing on the bottom is actually worth a pinch of shit, all those blocks – piff – it all falls over. What do they call it? The strands of a rope. They create all these strands of rope – but the rope wasn’t tied to anything.

“I don’t know where Ben and Olivia are. I’ve never met them, never seen them. They definitely never came on my boat and I definitely didn’t murder them. And they’ve basically dumped me in jail for half my lifetime – it must be coming up – for something I haven’t done. It’s destroyed my family and my life.”

The way he sees it, the most likely scenario is that Ben and Olivia did board a ketch, the classic-style two-masted 40ft wooden yacht with portholes and lots of ropework that Guy Wallace and another person on the Naiad, Hayden Morresey, described in detail. (Watson’s boat was a 26ft single-masted, home-built steel sloop with no portholes and no ropework.) Dozens of people reported a ketch matching Wallace and Morresey’s description – at Furneaux, in the Marlborough Sounds, and around New Zealand. But within days, police had ruled out the ketch, claiming Wallace and Morresey were mistaken. Watson says police tunnel vision meant they rapidly focused on him despite having no evidence, while discounting their best and most obvious lead.

“But how do I prove it? They have all these systems that stop you actually fixing what’s taken place. There’s a system in place where, even knowing they are wrong and have stuffed up, they never have to admit to it, or change the fact that they’ve stuffed up.

“I’m innocent. And the reason why I’m here is a bunch of bent cops, with big egos, wanting to have a stamp of, ‘We’ve solved this crime.’ And more importantly, the New Zealand public and the jury were just bullshitted from day one. They were lied to, over and over again, by these so-called wonderful men, these detectives. And it may have taken years to do it, but I’ve proved it – it’s proven.”

But still nothing changes.

In sentencing Watson, Justice Richard Heron said he must serve at least 17 years without parole – one for every year of Olivia’s short life. He’s done that time, but last July, the Parole Board dismissed Watson’s first application for freedom, relying on a psychologist’s report that claimed he had a “very high risk of violent recidivism” and suggested he had “ruminations of revenge”.

Ruminations of revenge?

“Nah, nah,” says Watson, shaking his head. “I need to go out and live my life. They’ve destroyed my life. I need to go out there and rebuild it somehow. You don’t have to forgive people, but you just know what they are about and you can get on with your own life.”

Getting on with any kind of normal life still rests in the hands of the Parole Board, and as long as he continues to protest he’s innocent, he’ll be accused of being in denial, being remorseless, being unrehabilitated – all of which reduce his chances of being released. He says a top prison official told him nearly a decade ago that he’d make sure Watson stayed in jail until he was 80.

“They’ll find any excuse to keep me in prison and they’re using their psychs to do it. It’s just part of a continuing character assassination. You can’t beat the system, coz it’s there to protect itself. One mate’s looking after the next mate.”

Among the public, Watson feels he has considerable sympathy. “Even the rednecks think basically, ‘Watson’s been demonised as this bad person, so he must be bad – but there’s something wrong with that case.’ Even the rednecks and the cop-lovers think that.”

An awful lot of people have supported his legal fight over the years, though, and he’s incredibly grateful to them. But if he’s ever going to be cleared, Watson says he needs help now from anyone

who’s able to lend it: witnesses who feel they were misled or their statements were inaccurate. Media there at the time who were fed information by the police. All the people who saw ketches, as described by Guy Wallace, whose information was rejected or not followed up. Police who’ve left the force and now have concerns about the investigation. Jurors who must now realise much of what he was convicted on has been disproved or undermined.

“What’s that old saying? ‘Evil can only triumph where good men do nothing’? Yeah. If they can actually think outside the square and see what happened, and what it is, and come forward. I’m this big monster and they’re not going to let go because they’ve got to admit they were wrong. And they’re not going to do it.”

Lawyer Kerry Cook says the most likely next legal step is to lodge a new application with the Governor-General for the royal prerogative of mercy.

Cook has been involved with Watson’s case for nearly five years, with Pip Hall, QC, providing oversight, and says the issues that alarmed him when he first looked at the case still remain. “The system’s saying there’s no doubt about his guilt, and I fundamentally disagree with that because of the many concerns that have been outlined. I just think that all of those issues we’ve raised lead a reasonable person to believe the conviction is unsafe and that it really needs to be quashed and then further examined.”

Cook says Watson’s convictions are an example of the system being reluctant to consider a miscarriage of justice may have occurred. “It really does boil down to those hairs, for me. That’s the only part that is constantly raised to support the safety of the convictions. But when you consider the issues surrounding them, as well as the other concerns about the evidence, I don’t think that’s a sufficient basis to continue to say these convictions are safe.”

Cook says they’re always looking for new evidence, “and people are constantly coming forward”.

To assist with that, Watson himself asks the politicians, the bureaucrats, the lawyers, the cops, the jurors – anyone who’s had any involvement with his case – to put themselves in his position: convicted and jailed for something they didn’t do. “Imagine if it was you this had happened to – or one of your kids. And the fact is, from just my experience, I know now it can happen to one of them, just as easily. It can happen to their son or daughter that gets shafted. My family and myself, we were just average people. “What did my old lawyer say? ‘Fair go – give the guy a fair go,’ I think he said to the jury. But it was too late, it was too gentle, I think.”

What would he say now?

“Give me some justice. Give me some honesty. But human nature’s a different story, isn’t it? People aren’t honest. People like Rob Pope and his band of merry men, they’ll never give me a fair go. “It’s 18 years that you never get back. What I’m more angry about is they’ve taken the best years of my life away, where I get to set myself up for having a life. Having a house, having a car and a bike and a boat. When I should’ve been working hard, saving my money, when you’re fit. Now I’m getting a sore back and what have you. And I think now, if I build my own house, how the hell am I going to carry things – I’ll stuff my back for six months if I’m picking up something.

“At some stage, whether it be when I’m 80 or next year, they’re going to dump me out on the street and I haven’t got a penny to my name. Own no clothes. They’ll dump me on the street with nothing.” He worries about getting a job if he’s ever let out, and says he needs someone to look past the image and give him a chance. He loved the forestry work he did when prisoners were allowed to work outside the wire and says people did give him a fair go. “I’ve never come across anyone with any issues, in here or when I was working on community gangs. Never. And they all knew who I was.”

Looking back to New Year’s Eve 1997, is there anything he regrets, anything he wishes he’d done differently? “Not gone to Furneaux Lodge? I think I shouldn’t have painted my boat the next day. But I’d planned to do it. No matter what I did, I think I was fucked. As soon as the boys from Christchurch turned up, I think I was fucked.”

This is what 18 years sounds like. It’s the sound of Watson, who’s never used a computer, never sent an email, never been on Google, describing his bewilderment at social media.

“People have dramas about this thing called Facebook and they’re calling people nasty words on it and what I don’t understand is how someone could be upset over someone calling them something on Facebook. Calling them a name on a computer? It’s all cold and impersonal. “On these things, for happiness or for it to be a joke, they put a smiley face. And the person at the other end puts LOL because they are wanting the person to laugh at the other end. It’s cold, impersonal. But obviously people fall in love on those internet things, too.”

It’s a long time ago, 1998. Jenny Shipley was Prime Minister. Taine Randell had just replaced Sean Fitzpatrick as All Blacks captain. Eighteen years. What would Ben and Olivia look like now? Where would their lives have taken them? What would they be doing right now? Eighteen years. It’s a long time for Scott Watson to have rehearsed all his alibis and answers, practised plausibility for questions about where he was and what he did that New Year.

Alternatively, it’s a long time to dwell on the injustice that’s been visited on him, a hell of a long time to be locked away from life. People can sift every word here, trying to divine whether Watson is being truthful or not, whether he’s guilty or innocent. But that’s a mug’s game best left for those who trust in psychics, Ouija boards and witch-sniffing. All that matters is the evidence. Not whether you like Scott Watson or not, or whether you disapprove of his language or tattoos or lifestyle. His attitude towards women or sense of humour may not be to everyone’s taste, but you could argue he’s hardly extraordinary there. You can point to some of the stories about him that have emerged from his time in prison, but most of them carry no weight when examined. And anyway, can you really expect someone to act normally in the most unnatural environment – especially if they feel they shouldn’t be there? We expect everyone to act like we would. But not everyone’s like us.

In the end, you can only make a judgment on what we know about the case – and also what we don’t know. We can rely on that evidence, or trust gut instinct and prejudice. Into that mix, all you can do is add what Scott Watson himself has to say. “Did I kill them? Did I kill Ben Smart and Olivia Hope? No. Do I know who did? No.” And that’s what he’s said for 18 years without hesitation or halt.

The sad thing is, Watson explains, there’s nothing really memorable in that time, none of life’s normal milestones that he imagined. Sometimes he lets himself wonder what his life would have held if none of this had ever happened. “Married with kids, going to work, a house, a boat, yeah, sailing. But then again, I might have sailed around the world. Gone on an adventure.”

In one of those early photos of Watson as he makes his way to court on a sunny morning in his suit and red tie, there’s a trace of a smile – or is it a grimace? Most versions of the photo are cropped, and you see him only from the chest up. But if you look closely at the full photo, you can see his left hand curled into a clench. Who mightn’t be uptight and angry, suspected of killing two young people, with the country’s media in your face? Who wouldn’t be angry still, if they’d lost their best years in prison for something they didn’t do?

“A guy asked me last night, ‘Has the time gone slow or has it gone fast?’ But – it’s just gone. Like I say, it’s time you never get back.”

For Scott Watson, this is what 18 years feels like.